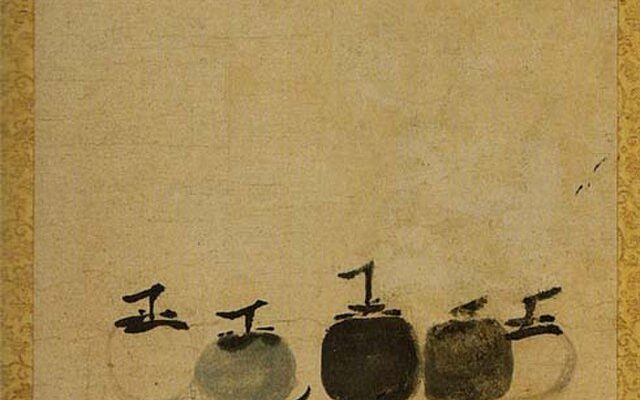

A 13th-century ink painting, that has been called the “Zen Mona Lisa,” will soon be making its world debut in the United States, leaving its ancient temple to be seen by the public for the first time. Going on display for a brief visit to the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, the display will mark a rare appearance outside Japan’s Daitokuji Ryokoin.

Muqi – Six Persimmons / Chestnuts

Two sides of the same scroll painted by the Chinese monk in the 13th century.

This is what Lévi-Strauss meant when he said that East Asia had understood “the poignancy of things”. pic.twitter.com/BVzH19MicY

— errant pilgrim (@winedark_sea) November 27, 2023

“Attributed to the 13th-century monk Muqi, Six Persimmons and Chestnuts are exquisitely subtle compositions painted in Song-dynasty China. At some point in the 15th or 16th century, they crossed the ocean to the hands of Japanese collectors who displayed them at tea gatherings, before being donated in the early 1600s to Daitokuji Ryokoin Zen temple in Kyoto, where they have been revered ever since. Apart from a brief exhibition at the Miho Museum outside Kyoto in 2019, both Six Persimmons and Chestnuts typically remain out of sight for those who are not members of their home temple community.

To people living in medieval and early modern Japan, the name Muqi was synonymous with Chinese-style painting (kara-e). Muqi was regarded with an almost unparalleled respect by the Japanese, who designated his mode of brushwork with the honorific term “priest’s style” (oshō-yō). Few painters in Japan escaped Muqi’s influence. This was especially true among artists of the Kano school, the large and influential collective that led the country’s production of ink painting in the Chinese style (kanga) for nearly five hundred years up to and through the 19th century, when Six Persimmons and Chestnuts in particular caught the attention — and admiration — of Western scholars who came to consider them as preeminent examples of Zen artworks,” The Asian Art Museum said in a statement to the public.

The works first came to Japan during the 1400s or 1500s, where they stayed until now. “Because they are quite delicate, the short time window will help protect the pieces from overexposure to light,” explains Smithsonian Magazine.

“The two paintings are the only pieces on display in the exhibition. The show is located in a large room with beige walls, soft lighting and a projection of the Daitokuji Ryokoin temple.

Yuki Morishima, the museum’s associate curator of Japanese art, said she was “starstruck” when she heard the artwork was coming to San Francisco. “When I was taking art history courses in school, these paintings were always discussed and in the textbooks.”

The two paintings will overlap for only three days, between December 8 to 10. The limited viewing time has been put into place to protect the delicate artworks from exposure to sunlight. The glass casing which holds the paintings is lined with silica gel to control humidity.

[Read More: Wild Prehistoric Battle Changes Everything We Thought]