The return of a single object—a gold pocket watch, long submerged in the cold silt of Lake Michigan—has resurrected not only the memory of a man but the full tragic weight of one of the Great Lakes’ deadliest catastrophes. After 165 years lost to the depths, the personal timepiece of British journalist and parliamentarian Herbert Ingram has made its improbable voyage home, delivered by hand to his native Boston, England, reports Smithsonian Magazine.

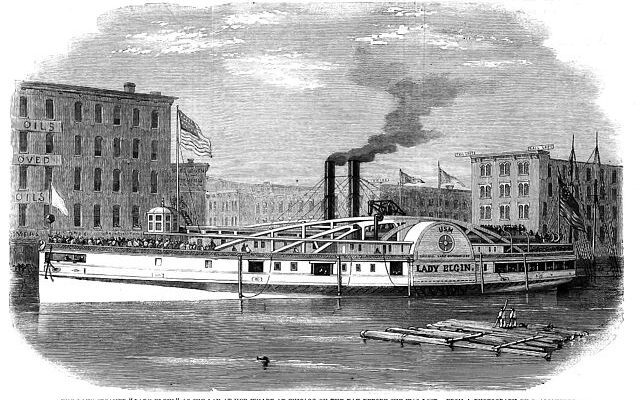

Ingram, founder of The Illustrated London News and a sitting member of Parliament, boarded the Lady Elgin in September 1860 as the only foreign passenger among a ship crowded with Irish-American militiamen—Union Guards raising funds for weapons, political purpose in tow. But in the early morning hours of September 8, under shrouded skies and poor visibility, the Lady Elgin was cleaved open by the lumber schooner Augusta. The militia’s rallying cries were silenced in minutes as the steamer split and sank beneath the waves off the coast of northern Illinois. Over 300 souls were lost. Ingram, though identified and repatriated to England, left one thing behind: his watch.

It remained there for over a century—buried in the debris field, time suspended. Not until 1992, when divers explored the wreck site located three years earlier near Highland Park, was the object retrieved: a gold-cased pocket watch, its chain intact, still affixed to a wax seal fob bearing the carved sardonyx initials “H.I.” It was a fragment not merely of personal property, but of personhood—a Victorian man’s most intimate signature of presence, used to seal letters, validate agreements, and mark time in an era obsessed with the measured march of progress.

The wreck itself had passed through controversy. When Congress enacted the Abandoned Shipwreck Act of 1988, it declared sunken ships state property. But private salvor Harry Zych argued—successfully—that the Lady Elgin had never been legally abandoned. Thus it remains, anomalously, one of the only privately held wrecks on the Great Lakes, and a reminder that the boundary between public memory and private ownership is as murky as the lake’s benthic floor.

Enter Valerie van Heest, maritime historian and co-founder of the Michigan Shipwreck Research Association, who once helped document the wreck in the 1990s and recently acquired the watch. Recognizing the fob’s unique markings and the singular identity of its owner, she took it upon herself to deliver the watch not to a museum in Chicago, not to a collector, but to Ingram’s hometown—where a statue of the man still surveys the square. There, curators were preparing an exhibition on Ingram’s journalistic and political career, yet lacked any physical trace of the man. The watch arrived like a visitation.

“Returning this watch is the right thing to do,” van Heest said in an interview. “This is reminding people that shipwrecks affected people, affected families, and this shows that 165 years later, we care. People care about the individuals lost.”

The reception in Boston was rapturous. “Since then I’ve been absolutely buzzing,” said Councilwoman Sarah Sharpe, who leads the town’s heritage work. “Herbert Ingram was one of our most influential people.”

The return of Ingram’s watch reaffirms a truth rarely spoken in the age of high-speed forgetting: that history is not merely composed of events, but of objects—weighty, intimate, imperishable—and that sometimes, the things we lose become the only means by which we remember.